# Summary

Advanced persistent threat (APT) attacks have caused serious security threats and economic losses worldwide. Various real-time detection mechanisms combining contextual information and source graphs have been proposed to defend against APT attacks. However, existing real-time APT detection mechanisms face accuracy and efficiency issues due to inaccurate detection models and increasing source map sizes. To address the accuracy issue, we propose a novel and accurate APT detection model that eliminates unnecessary stages and focuses on the remaining stages with improved definitions. To address the efficiency issue, we propose a state-based framework where events are consumed as streams and each entity is represented in an FSA-like structure without storing historical data. Furthermore, we reconstruct the attack scenario by storing only one thousandth of the events in the database. Finally, we implemented our design CONAN on Windows and conducted comprehensive experiments in real-world scenarios to show that CONAN can accurately and effectively detect all attacks within the scope of our evaluation. CONAN’s memory usage and CPU efficiency remain constant over time (1-10 MB of memory, hundreds of times faster than data generation), making CONAN a practical design for detecting known and unknown APT attacks in real-world scenarios.

# Research background

Traditional intrusion detection methods can be divided into two categories: offline and online. One of the most well-known offline detection methods is the sandbox method, which deploys the target program into an isolated environment for individual analysis. Additionally, multiple logging and provenance tracking systems are built to monitor the system’s activity, and then provenance graphs are built to detect or analyze attacks. Although these methods can clearly see the attack, considering the lag of offline detection, people began to use online detection methods to detect attacks in real time. These methods include network traffic-based analysis, software static feature detection and hook technology. However, existing research mainly focuses on a specific stage of APT, and the intrinsic mechanism and attack vector of APT are still poorly understood.

Recent work has demonstrated the effectiveness of context-based detection. Real-time detection systems using context methods have been proposed in recent years. StreamSpot analyzes streaming information flow graphs to detect anomalous activity by extracting local graph features and vectorizing them for classification. Learning-based detection methods can only provide malicious scores or classification results, but cannot interpret these results. Additionally, these detection systems cannot detect attacks without false positives. Therefore, in practice, learning-based approaches are not suitable for enterprise scenarios. Sleuth then proposed a label-based detection method based on the provenance graph, but this method mainly focused on suspicious access to confidential files and reduced false positives by adding domain whitelisting. To better understand APT attacks, analysts decouple the APT life cycle into multiple stages and then use the characteristics corresponding to each stage to match suspicious behavior. APT attacks are divided into seven or eleven stages. The multi-stage kill chain model approach is adopted by many researchers. Holmes has made substantial progress in stage-based detection by building models that detect each stage based on simple rules and calculate a suspicious score. However, not all of these stages are necessary in an APT attack (e.g., credential access), and some of them (e.g., detection of remote code execution vulnerabilities) are often detected with prior knowledge and tend to change over time.

Furthermore, real-time context work often preserves context information in the source graph. However, as the graph grows over time, APT can persist for months or even years, making these methods inevitably encounter efficiency and memory issues when the system runs for a long time, especially for real-time detection. Therefore, most detection methods rely on short time windows.

To address these challenges, especially in terms of accuracy and efficiency, this paper proposes a model for accurate APT detection. Furthermore, it proposes a novel state-based detection framework, where each process and file is represented as a carefully designed data structure for real-time, long-term detection.

To detect unknown APTs with high accuracy, we leverage control flow (i.e., why a process or code is executed) and data flow (i.e., how data is delivered), rather than focusing on unnecessary, undetectable, and easily changeable stages of an APT attack. between objects) to explain contextual behavior. We identified the following three basic attack stages: 1) deploy and execute the attacker’s code, 2) collect sensitive information or cause damage, and 3) communicate with the C&C server or exfiltrate sensitive data. We mainly focus on accurately detecting these stages and combining them to distinguish malicious from benign behavior. This approach facilitates accurate detection of unknown APTs compared to more complex stage-based modules.

In order to perform context detection efficiently in real time, we propose a novel state-based tracking and detection framework and corresponding data structures based on the idea of forensic analysis. In this design, all semantics are stored as state, and the framework only retains the current state of all processes and files for instrumentation. The state is updated by events and related states of other entities, similar to Finite State Automata (FSA), which we call FSA-like structures. Therefore, the framework does not need to store historical data and memory usage remains consistent. Status changes over time. Once a process becomes malicious, it will be detected no matter how long the attack lasts. Using this framework, we can monitor hosts over long periods of time to automatically detect APTs with high accuracy and low overhead.

Furthermore, our detection method based on this framework can detect attacks and provide explanations. Specifically, detection results are generated through reconstructed attack graphs, which illustrate how these attacks occur and facilitate subsequent analysis.

Main contributions:

- Propose a new APT detection model that focuses on three constant steps of APT, and we propose a set of designs to accurately track and detect these steps, including detecting memory-based attacks and suspicious process behavior.

- A novel and efficient state-based detection framework is proposed, where each process and file is represented as an FSA-like structure. The framework helps detect APTs that have constant and limited memory usage (1-10 MB) and are efficient (hundreds of times faster than data generation).

- Implemented as an APT attack detection system, which can detect unknown advanced attacks in real time with high accuracy and quickly recover the attack chain. We tested our system on real-world datasets and determined that it performed better than previous methods, especially in terms of efficiency and accuracy.

# Research questions

The letter A in APT represents the advanced techniques used in these attacks. Traditional detection systems, including malware detection, vulnerability detection and threat intelligence, only focus on a single stage of the APT attack chain, and the attack techniques used in these stages are easily changed; therefore, APT attackers can easily circumvent these traditional detection methods. MITER ATT&CK introduced the eleven-stage APT attack model to describe the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) used in APT attacks.

However, overly complex multiphase models can only be used to better understand APTs, not to detect them. For example, the authors of Holmes developed a system to detect techniques within each strategy (stage) and connect these stages as an attack chain through information flow (including data flow and control flow). In each attack chain, the more stages detected, the more likely the attack is. However, there are three main problems.

- Hundreds of techniques are used at each stage. The system must detect hundreds of technologies, which is difficult to implement and results in high detection overhead.

- Still consider the detection points of traditional methods, such as vulnerabilities. In order to detect these stages, prior knowledge is required.

- The techniques used in attacks change easily, making it difficult to detect unknown attacks.

Finally, the authors believe that although they were unable to accurately detect all stages, as a subset of all stages, the detected stages were sufficient to distinguish attacks from benign activities. In other words, it is not necessary to detect all phases. Furthermore, introducing some common and unnecessary stages increases the false positive rate.

A large number of phases cannot indicate an attack, and a small number of phases cannot prove its legitimacy. For example, a newly installed browser can trigger 6 stages of the MITER ATT&CK eleven-stage model (initial access, execution, persistence, credential access, discovery, and exfiltration) and will trigger error alerts [22]. Meanwhile, advanced attackers gain access to machines and download malware via zero-day vulnerabilities. It then uses unknown methods to achieve persistence (or in some cases where persistence is not desired, such as on a server that never shuts down). It logs keystrokes and exfiltrate data through command and control channels, which can be difficult to detect. Finally, the only detectable stages in this attack are execution and collection, so they cannot be considered attacks.

# APT detection three-stage model

To detect unknown APT attacks, we first find their invariant parts. In other words, we try to answer the question: what causes these active “attacks”. After studying hundreds of APT attacks, it can first be observed that the attacker must first deploy their code onto the victim. The difference is that malware can be customized or executed solely in memory to evade traditional static file-based detection systems. The second observation is that the attackers’ end goal has remained the same over the years. Since 2006, APT1 has introduced attacks that have stolen hundreds of terabytes of data from at least 141 organizations. Today, APT38 is focused on similar tasks. These behaviors are similar to permissions in Android and can lead to privacy leaks or corruption. The final observation is that the attacker will communicate with the C&C server and steal confidential data, and the malicious program should always have the ability to access the network.

- **Deploy and execute the attacker’s code. ** Any process behavior is the result of code execution. An attacker must first deploy code to a victim to achieve their goal. To detect this stage, we monitor data flows from external sources, including networks and portable devices, which we refer to as untrusted data flows. Having an untrusted data flow is necessary to launch an attack, regardless of what vulnerabilities or techniques attackers use to deploy their code. This design may result in more false positives, but the techniques described in subsequent chapters will help resolve this issue. In another case, an attacker may use legitimate processes to achieve his goals. For example, an attacker could use the preinstalled Windows SnappingTool to capture the screen. This is where untrusted control flow can help. If a process or thread is started by a suspicious thread, the process or thread is also marked as suspicious. Code deployment is always necessary unless the attacker can gain authorized access to the victim through other means (for example, by logging in remotely using a password). This type of attack can be prevented through IP whitelisting and detected through anomaly detection, which is beyond the scope of this article.

Monitor data flows from outside? Does it mean that the data source is not just log data? But in the form of traffic + logs?

-

**Collect sensitive information or cause damage. ** Attackers are usually trying to steal confidential data or damage the victim’s data or machine, which is why attackers carry out attacks and why victims want to avoid this outcome. We do not consider intrusions that reach the victim but do not result in harmful behavior to be true attacks. Theft of confidential data from files can be detected by monitoring data streams from confidential targets as confidential data streams. **Other suspicious behavior is detected by signatures predefined by the author. **

-

**Communicate with C&C servers or leak sensitive data. ** Both of these actions are required in the APT, without which the attack cannot be completed. While there are many ways to achieve this (e.g., removable disks), a typical real-world attack method is over a network connection.

These three stages are simple and necessary for most APT attacks. Therefore, we try to detect processes that execute suspicious code for malicious behavior. Additionally, we provide additional features to illustrate different attack scenarios. Unlike previous work, we do not assign scores or simple labels; instead, we use more detailed descriptions to describe the components of the attack for better understanding and further analysis without additional overhead.

# Track suspicious code execution

Memory-based attacks, including injection and fileless attacks, can help attackers execute code in the memory of benign applications. These attacks are increasingly used because traditional detection systems are blind to them. Although existing research treats processes as entities that store contextual information, they are vulnerable to memory-based attacks. Detection techniques used in memory-based attacks can be helpful, but there are multiple ways to implement these attacks, making detection difficult. Therefore, in this section, a method is proposed to detect suspicious code execution by tracing the suspicious data flow and examining the execution call stack, ignoring the technique used in the attack.

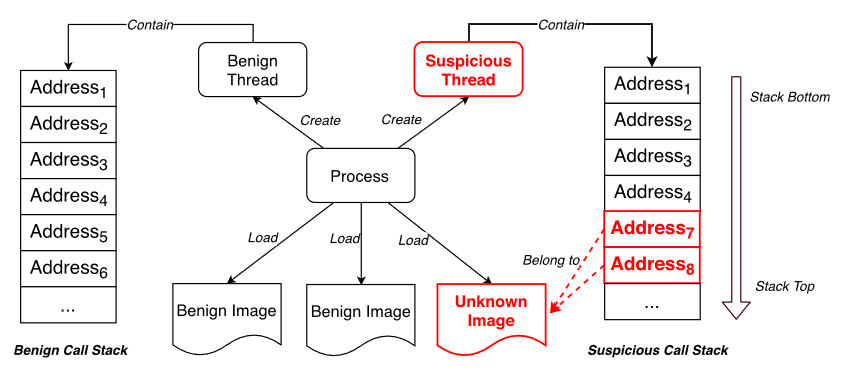

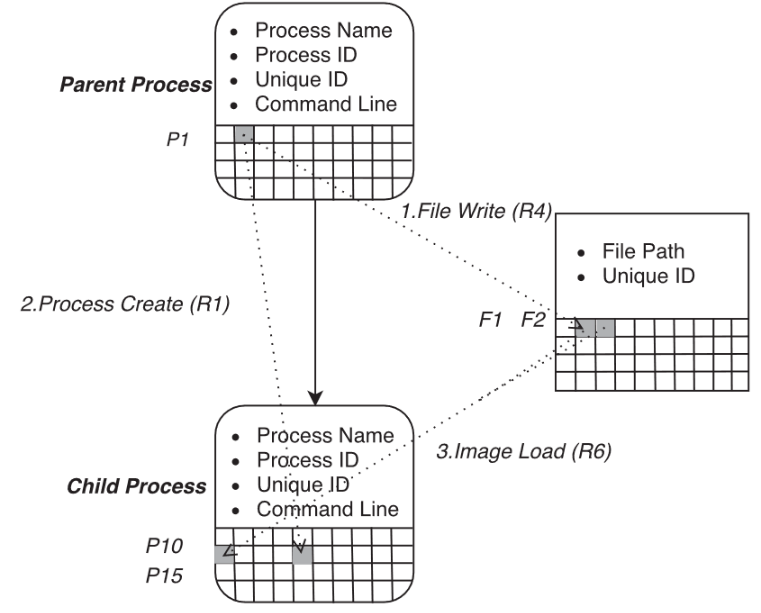

If an attacker wants to perform malicious behavior, he must 1) execute malicious code directly or 2) do so with the help of a benign process. The main challenge in detection is determining **1) what code was executed, 2) where it came from, and 3) how it was executed. ** Although taint tracking is very helpful when tracking fine-grained data flows, this method cannot be used in real-time due to its high overhead. To solve the first challenge, we employ a call stack. The call stack is a stack data structure used to store information about the active subroutine when an event is generated. The addresses in the call stack are return addresses belonging to different blocks of code (eg images). If all addresses in a call stack come from trusted code blocks, we say that the thread executes trusted code. Since benign processes can easily be forced to execute external code, we divide the process into subunits (threads) based on code execution. As shown in Figure 1, these threads executing unknown or suspicious code are separate from completely benign threads. We consider the following scenario:

(1) Image loading and memory execution. Image loading is the basic operation by which a process loads an executable file into its memory. An attacker can replace a benign image file with a malicious image file, or force a benign application to load a malicious image and then perform the attack under the guise of a benign process. Additionally, an attacker could write malicious code directly into another process’s memory space, or load an image from memory instead of disk without triggering a system event. The former is called process injection and is commonly used in attacks, and the latter is a technique called reflective loading that has been used in recent advanced attacks. Our system monitors dynamic events for loading images and stores the base address and size of memory allocated by each process. When the memory address of an unsigned image or allocated memory appears in the call stack, it means that some unknown code is executed in this thread; therefore, this thread should be separated from other threads. To reduce the overhead in parsing the full call stack, we perform low-frequency sample checks per thread.

(2) Script execution. Script-based attacks have become common in recent years because the host process is entirely benign and the process reads and executes code (such as PowerShell and VBscript) instead of loading it. Detecting such attacks is challenging. Our system enumerates most common script hosts and handles them separately from normal processes.

To address the second challenge, we track suspicious data through coarse-grained data flow-based inference. For example, if a process has a network connection, any files written by the process may contain data from the network.

To address the third challenge, we trace control flow (especially processes created by suspicious threads). Although they may be benign processes, they can be used to achieve attackers’ goals, such as screen scraping and exfiltration of sensitive data.

# Method overview

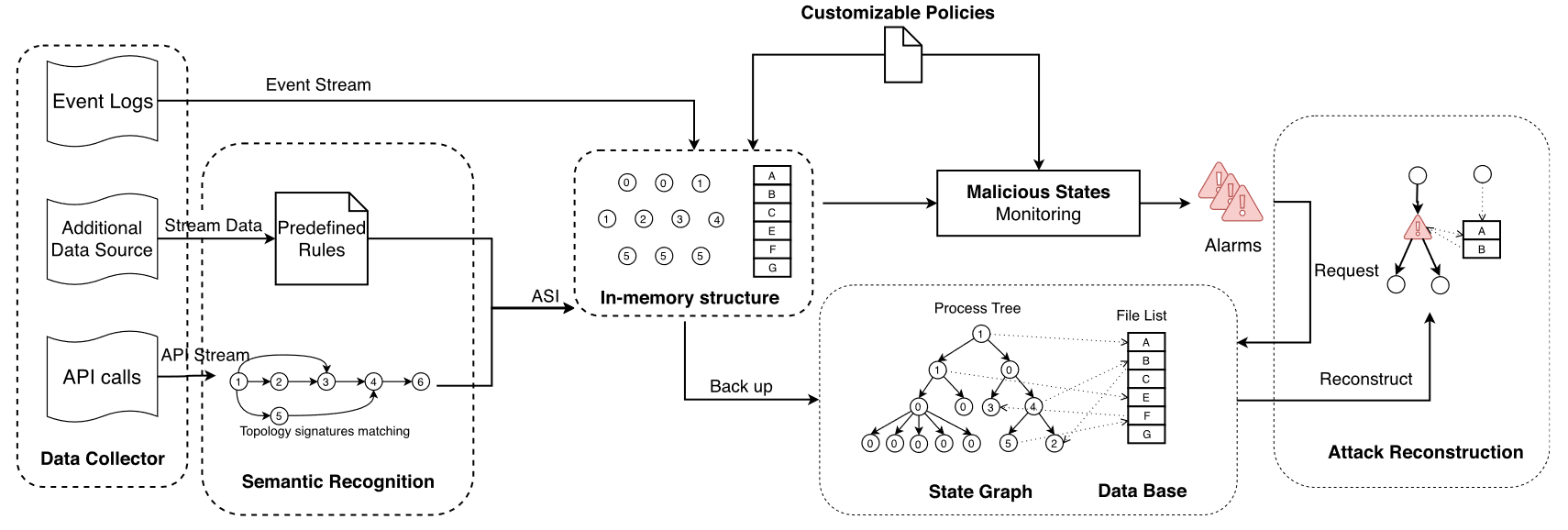

As shown in Figure 2, this paper develops a fast and stable multi-level data collector on the host to collect audit trails, call stacks and other data. This data is then sent to the instrumentation server, extracted as high-level semantics and stored in memory structures as process and file state. At the same time, all event logs are processed according to predefined rules to change the status of processes and files. These events and status are stored in a database for later reconstruction by attacks. Whenever a process enters a malicious state, an alert is triggered along with a reconstructed attack graph. The detection model we propose here enables the system to accurately detect APTs, and the state-based framework makes it possible to detect APTs efficiently.

The detection model proposed here enables the system to accurately detect APT, and the state-based framework makes it possible to detect APT efficiently.

The letter P in APT stands for Persistence, which means the attacker can lie dormant for a long time until he gets what he wants. This is different from the same term introduced in the attack chain model, which represents techniques that enable malware to launch automatically after an operating system restarts. Techniques for detecting persistence are not practical. For one thing, there are 59 known persistence technologies, and detecting all of them can be expensive. On the other hand, even if a process is detected to be persistent, it cannot be considered malware. An attacker can lie dormant for a long time without appearing to behave suspiciously. Additionally, malicious files may be opened days after being downloaded. Therefore, it is difficult to detect attacks based on contextual information.

# Semantic recognition

Semantic state definitions are inspired by forensic analysis; we automatically identify high-level semantics for data flow, control flow, and process behavior. These semantics represent the basic evidence used in context-based detection. We call this semantics Atomic Suspicious Indicator (ASI).

ASI includes one of the following types of semantics and is detected or inferred through the corresponding traces:

- Actions performed by an attacker to achieve their goals. Typically detected by API or inferred from confidential data streams.

- The origin of the suspicious code, in other words, the reason why the process is able to perform such behavior; inferred from untrusted data flows.

- The ability to infer external communications through network activity.

- Infer the cause of process execution through untrusted control flow.

- Describe additional characteristics of the attack.

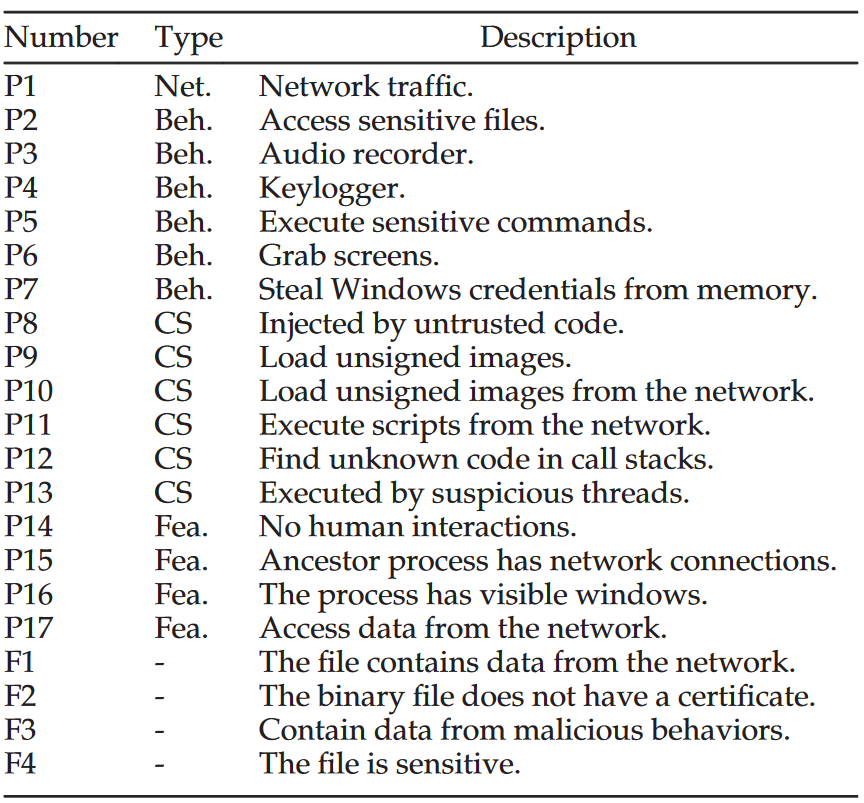

Each ASI can be described as a triplet $<N_o;T_y;D_e>$. Each ASI is assigned a unique number $N_o$, which represents its position in the bitmap of the recorded state. $T_y$ represents categories, including the following categories: 1) Suspicious code sources, tracking potential untrusted code execution; 2) Suspicious behaviors; 3) Network connections; 4) Features, which are additional features that illustrate different attack scenarios. $D_e$ represents a description used to interpret detection results in human-readable semantics.

These ASIs are identified by extraction directly from the source data or by inference from rules. A new ASI that can help detect APTs should be declared if: 1) it has different semantics than an existing ASI, or 2) there are multiple ways to identify the same semantics with varying accuracy.

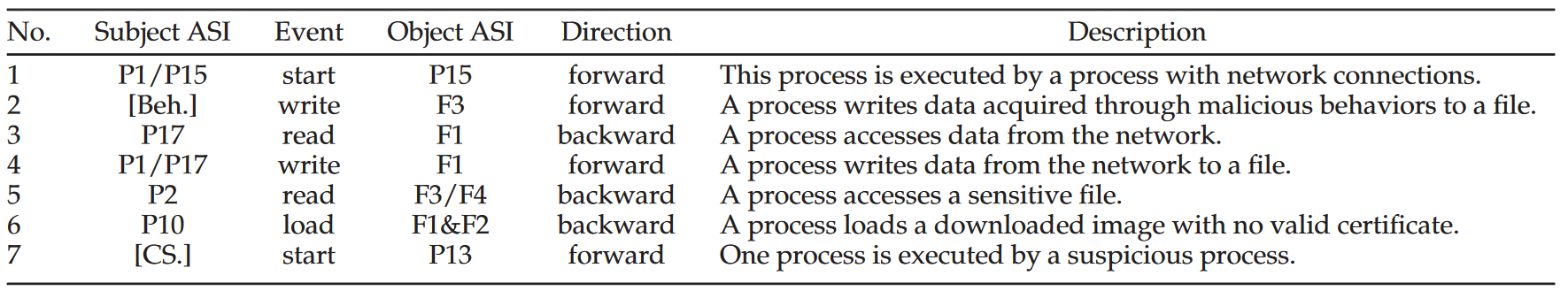

The first column is the ASI number of the process (P) or file (F). ASI is classified by type: Code Source (CS), Behavior (Beh.), Features (Fea.) and Network (Net.)

The combination of different ASIs can ultimately describe different attack scenarios. The following detection steps are based on these ASIs, data flows, and control flows.

Some ASIs can be easily detected or generated through inference based on system event logs. Although the actions commonly performed by attackers are among the most important ASIs, there are currently no proven methods to detect them.

In order to efficiently match these topology API signatures in real time, we convert these topologies into FSA to match the signatures with streaming data, and these APIs should be matched within a window to reduce false alarms. In practical applications, we use a 6-second time window. We do not use system calls because they are too low level to reflect the semantics.

API calls are usually recorded through sandboxed API hooking, which cannot be used in real-time detection systems due to its poor performance and stability. We use ETW kernel call stack traces to recover API calls. ETW can capture kernel events (including SysCallEnter events, which represent calls to system calls) and their call stacks. We effectively restore the API from the call stack. However, this process is not our main contribution and we do not describe it in detail here.

# Data structure

To support real-time analysis and long-term monitoring, we propose a main-memory FSA-like structure to record the status of each process and file that may be involved in the attack. Note that we do not need to store any historical events to perform detection, but for the additional goal of reconstructing the attack, we only keep a small set of events that caused state changes to the database.

As shown in Figure 3, when each process and file is in a specific state, we save their basic information and status in memory.

All inactive processes and files are removed from memory to the database to ensure constant memory. It will only be restored if the file is manipulated by another process.

# State transfer

Events of the same type have different high-level semantics depending on the differences between the subjects and objects involved. For example, reading a downloaded file is different from reading a file that exists in your personal directory. The former involves accessing unknown data sources, which may lead to untrusted code execution, while the latter involves accessing personal data, which may ultimately lead to user data leakage. The purpose of this section is to track confidential data flows, untrusted data flows, and untrusted control flows.

In order to automatically distinguish these events and record semantics, a set of predefined rules was created to assign more detailed semantics to events, and a selected set of rules can be found in Table 2 .

Each rule is a six-tuple: $<N_o;S_s;E_v;S_o;D_i;D_e>$. $N_o$ is the sequence number of the rule, which is used in the edge to indicate how this operation is generated. $S_s$ represents a specific state of the agent, which is always a process in our design. $S_o$ represents the specific state of an object, which is a process, a file or an IP. $E_v$ is an event performed by the subject on the object. $D_i$, forward or backward, indicates the direction in which one entity affects another entity. When a subject is in a certain state and performs an event on an object, the state of the object undergoes what we call a positive change, where the subject and object are the source and destination respectively. On the contrary, if the subject is affected by the object, we call it backward; in this case, the subject is the destination. Note that when $S_s$ and $S_o$ are used as sources, they can both be in one or more states. $D_e$ is a description of the purpose of the rule, used to explain the reconstructed attack chain.

Each entity (i.e. subject or object) in the system is like an FSA and can be described as a five-tuple: $<S;\Sigma;\delta;S_0;F>$.

S: state set. The bit combination in $S_t$ represents the current status of the process and file.

$\Sigma$: Enter the alphabet. Consists of system events $E_v$.

$\delta$: state transition function.

$S_0$: initial state. As soon as a new process or file appears in our system, we create a corresponding instance in memory. All bits in $S_t$ are set to false. Only files that may contain confidential data are initialized with status F5.

F: Final state set. Once a process enters one of these states, an alert is triggered.

However, in order to reconstruct the attack for better understanding and further analysis, we store the events leading to the state change into a database. The event store has four attributes: Rule number, timestamp, source and destination. The rule number represents the reason for the status change. Events are like edges in an origin graph, but the sources and destinations of operations are the bits in the bitmap used to record state, rather than processes or files.

# Malicious status

Malicious states are various combinations of individual states indicating contextual information required for detection. ASIs can be divided into 4 different types: Suspicious Code Sources, Network Connections, and Suspicious Behaviors and Characteristics . We say a process enters a malicious state if it contains at least one ASI from each of the first three categories (excluding signatures). Each malicious state illustrates a different attack scenario. For example, if a process loads an unsigned image downloaded from the network, performs malicious behavior, and connects to the network, we identify it as a “download and execute” attack and understand the attacker’s goals based on the malicious behavior it performs. If an unsigned image already exists on the host, it can be identified as “existing malware”. Therefore, we do not need to assume that all stages of the attack occur after CONAN starts monitoring the system, which we consider to be an improvement over existing work by CONAN.

As soon as a process enters one of these malicious states, our system will sound an alert. In other words, all detection progress can be expressed by checking the status of a process. For example, such a check could reveal whether a process is executing unsigned code from the network. We don’t need to know the exact origin of the code, as this information is of little help for detection. Furthermore, since our system only checks process status, it has much lower overhead than graph-based detection mechanisms but achieves almost the same effect.

We also leverage several common features to identify different attack scenarios. For example, the “human-computer interaction” feature reflects whether the process runs automatically, and the “no visible window” feature indicates whether the user can clearly identify the existence of the process. The more features, the higher the confidence of malicious behavior, representing different attack scenarios. The use of more features will help system administrators analyze attacks and reduce false positives. Please note that we do not use any whitelisting of files, processes or domains other than code authentication. Malware installed before our systems are deployed can also be detected as special attack scenarios.

# Attack reconstruction

Source analysis greatly aids in understanding and detecting attacks. Therefore, we not only detect these malicious attacks, but also try to reconstruct them semantically, similar to the functionality of source analysis. Such reconstructions help greatly improve attack analysis, further reducing false positives and helping to protect hosts from future attacks.

Due to the special nature of our data structures, these tasks can be performed efficiently. Because we aggregate all evidence of the target process into state, the basic idea of the reconstruction attack is to explain why the process is classified as malicious, specifically, by backtracking to the source of the ASI in the process. Because our system keeps the source of each ASI in the database as edges between states, the source of the attack can be found in linear time through edge backtracking. For forward analysis, suspicious processes cause little additional impact since our system can detect malicious processes immediately; therefore, there is no dependency explosion with forward tracing.

In practice, reconstructed graphs with dependency explosion contribute less to further analysis. To obtain this graph, we reconstruct only enough evidence to prove that this is an attack, rather than trying to reconstruct the entire attack, since tracking attacks on coarse-grained data flows is an unsolved research problem that has been studied for many years.

# Experimental evaluation

Three different environment long runs were used to evaluate CONAN on Windows. The results show that CONAN can detect multiple types of attacks with high accuracy and low overhead.

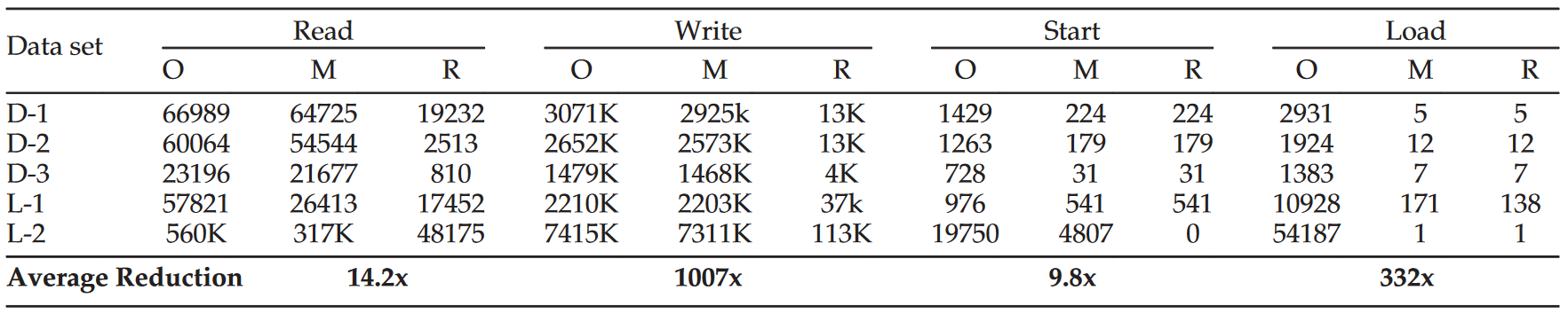

Since nearly 99.9% of system events are related to benign activities, it is important to reduce irrelevant data to maintain the efficiency and accuracy of CONAN. As mentioned above, we use predefined rules to identify the high-level semantics of system events. Table 3 shows the number of events between different process steps: original events (O), matching rules (M), and rules that caused a status change and were stored in the database (R). The numbers in column M are similar to the numbers in column O, which means that CONAN tracked most of the original events. The number in column M means that less than 1% of the data is stored for reconstruction. Duplicate read events are pre-filtered.

# Summary discussion

How an attacker on a CONAN system attempts to evade detection mechanisms.

In-memory attack. The address in the call stack is the entry point for the next command. To avoid suspicious addresses in the call stack, malicious code cannot call any APIs that cause kernel events (such as reading/writing files, system calls, and memory operations). But in our experience, without these APIs, attackers cannot achieve their goals. Another possible approach is to hook or insert malicious code into benign images; these attacks will also be logged at the outset due to memory manipulation. Furthermore, it describes a research problem called memory authentication. Another type of attack that CONAN cannot detect is a ROP attack.

System expansion. There is more than one way to achieve suspicious behavior, which means we should develop corresponding signatures for each implementation. For example, existing research describes three methods for taking screenshots on Windows, and there are a few others. However, the total number of implementations is limited by the operating system itself and is far less than the number of attacks. Therefore, monitoring other behaviors and their implementation is feasible and worthwhile. Additionally, our system relies primarily on tracing the flow of information to determine why code was executed and where sensitive information went. Our system can be easily expanded by adding more data sources and corresponding rules to cover more information flows.

System recovery. Since our detection method is state-based, it is important to recover the state when the system crashes or reboots. Since all state is stored in the database, it can be recovered from a crash. When an entity’s state changes, it is synchronized to the database. When an entity is deleted, it is marked as having no data in the database. So when our system restarts, it restores the in-memory state from the database and the system is able to continue its work.

Whitelist. Our whitelisting mechanism based on code certification works well in DARPA engagement and in our labs, i.e. zero false positives. However, we will receive some false positives in real-life scenarios. To further reduce these false positives, we can combine existing whitelisting mechanisms with process and/or IP whitelisting mechanisms, which have been shown to be effective in the literature.

Figure reconstruction. Because CONAN only retains the first event that causes a state change, it misses subsequent events that have the same impact on the entity. Therefore, the reconstructed graph may be incomplete. We consider this approach because the main purpose of our system is to detect attacks accurately and efficiently, and the reconstructed graph is only used to understand why the detection signal is generated. Another option is to delete duplicate events as they are inserted into the database. In this case, duplicate means that both the source and destination of the event, and the matching rules are the same. In order to determine whether an event is repeated, we must store and search it, which requires both memory storage and CPU calculations. In our method, we only need to check the state of an entity to decide whether to store the event. It is much lighter weight.

# Literature comparison

Host intrusion detection techniques can be divided into three detector types: misuse, anomaly, or hybrid.

Misuse detection mainly relies on known attack patterns; the raw data collected is converted into an established format and then passed to the detection module, which makes a decision. Unfortunately, misuse detection techniques have difficulty detecting unknown attacks (i.e., zero-day attacks). Knowledge-based methods rely on attack signature databases that need to be updated regularly, while machine learning-based methods often lack generalization capabilities. Anomaly detection is used to detect unknown attacks. Behavioral profiles of benign programs are stored and updated frequently. Any deviation from the configuration file will be flagged as a potential attack. The advantage of anomaly-based techniques is that they can detect zero-day attacks, but these methods result in many false positives because misuse detection and anomaly detection cannot account for both false positives and false positives. Considering the shortcomings of the above two methods, a hybrid technique is proposed.

In addition to combining misuse detection and anomaly detection techniques, hybrid techniques also involve specific strategies. Policy-based approaches are well designed, as exemplified by SLEUTH and HOLMES. SLEUTH utilizes trust tags and confidentiality tags to define code and data. HOLMES builds custom strategies to exploit the semantics of each step in the APT attack chain. The above works rarely discuss the essential intent of the attack lifecycle, resulting in some false alarms or false negatives remaining.

Conan is very different from previous designs. This article proposes a detection model that summarizes the three basic stages present in APT attacks. With this model, the entire attack chain can be revealed and potential hazards accurately detected.

Provenance tracing is designed to discover the complete attack path in complex contexts. Backtracing is a common solution used in previous work and was inspired by the seminal work BackTracker. PriorTracker has since optimized the process proposed in and enabled forward tracking capabilities for timely attack causality analysis. During the forward/backward search process, a provenance graph is constructed to record system object/topic dependencies. Research exploits system call data to track information flow. In order to improve accuracy, new research collects fine-grained data, but blindly increasing the amount of data results in increased overhead. SLEUTH innovates by using tags for efficient event storage and analysis, but the proposed strategy has inherent limitations. While SLEUTH maintains a whitelist of internal IP addresses that are not tagged untrusted sources (DNS lookups, etc.), which requires frequent maintenance to reduce false positives, the tag-based approach is essentially a graph-based storage method and is difficult to deal with long-term APT attacks. Since SLEUTH takes a long time to process the dependencies of large amounts of data, it is difficult to guarantee real-time performance. The amount of data is directly proportional to memory consumption, and growing data can cause memory explosion.

Unlike previous work, CONAN makes good use of the concept of provenance graphs for real-time detection. CONAN adopts a novel state-based framework with constant memory usage and low overhead. Our system is context-sensitive and introduces an FSM-like structure to automatically transfer state. Additionally, we can analyze audit data, perform state transitions, and generate alerts in real-time regardless of how long the APT attack lasts.