# Link-free link prediction through relation distillation

Graph Neural Networks (GNN) have shown excellent performance in link prediction tasks. Although graph neural networks are very efficient, the high latency introduced by their non-triangular neighborhood data dependence limits the practical deployment of graph neural networks. On the contrary, the known efficient MLP is far less effective than GNN due to the lack of relational knowledge. In this work, to combine the advantages of GNN and MLP, we first explore direct knowledge distillation (KD) methods for link prediction, namely prediction logit-based matching and node representation-based matching. After observing that direct KD-like methods perform poorly in link prediction, we propose a relational KD framework, link-less link prediction (LLP), to leverage MLP for knowledge distillation of link prediction. Unlike simple KD methods that match independent link pairs or node representations, LLP distills relational knowledge centered on each (anchor) node into a student MLP. Specifically, we propose rank-based matching and distribution-based matching strategies, which complement each other. Extensive experiments demonstrate that LLP significantly improves the link prediction performance of MLP, even outperforming teacher GNN on 7 out of 8 benchmarks. On the large-scale OGB dataset, LLP’s link prediction inference speed is 70.68 times faster than that of GNN.

# Introduction

Graph neural networks (GNN) have been widely used for machine learning on graph-structured data (Kipf & Welling, 2016a; Hamilton et al., 2017). They have shown remarkable performance in various applications such as node classification (Veliˇ ckovi ́ c et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020), graph classification (Zhang et al., 2018), graph generation (You et al., 2018; Shiao & Papalexakis, 2021), and link prediction (Zhang & Chen, 2018; Shiao et al., 2023).

Among them, link prediction is a significant key issue in the field of graph machine learning, whose purpose is to predict the possibility of any two nodes forming a link. It has a wide range of practical applications, such as the completion of knowledge graphs (Schlichtkrull et al., 2018; Nathani et al., 2019; Vashishth et al., 2020), friend recommendations on social platforms (Sankar et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022; Fan et al., 2022), and user item recommendations on service and business platforms (Koren et al., 2009; Ying et al., 2009). et al., 2018a; He et al., 2020). With the increasing popularity of GNNs, the most advanced link prediction methods adopt an encoder-decoder style model, where the encoder is a GNN and the decoder is directly applied to the node representation pairs learned by the GNN (Kipf & Welling, 2016b; Zhang & Chen, 2018; Cai & Ji, 2020; Zhao et al., 2022b).

The success of GNNs is often attributed to the explicit use of contextual information from the neighborhood surrounding a node (Zhang et al., 2020e). However, compared with tabular models such as multilayer perceptrons (MLP), this leads to a heavy reliance on neighborhood acquisition and aggregation schemes, especially due to neighborhood explosion, resulting in high time costs for training and inference (Zhang et al., 2020b; Jia et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021b; Zeng et al., 2019). Compared with GNNs, MLPs do not require any graph topology information and are therefore more suitable for new nodes or isolated nodes (such as cold start settings), but often lead to poorer general task performance of the encoder, which we also empirically verify in Section 4. Nonetheless, the absence of graph dependence makes the training and inference time of MLP negligible compared to GNN. Therefore, MLP remains a dominant choice in large-scale applications requiring fast real-time inference (Zhang et al., 2021b; Covington et al., 2016; Gholami et al., 2021).

Given these speed versus performance trade-offs, several recent studies have proposed utilizing knowledge distillation (KD) techniques to transfer learned knowledge from GNNs to MLPs (Hinton et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2021b; Zheng et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2021)) to take advantage of the performance advantages of GNNs and the speed advantages of MLPs. Specifically, in this way, it is possible for student MLPs to acquire graph context knowledge propagated through KD from GNN teachers, thereby not only performing better in practice but also enjoying model latency advantages compared to GNNs, such as in production inference settings. However, these studies mainly focus on node or layer tasks. Given that KD in the link prediction task has not yet been explored and there are a large number of link prediction problems in recommender systems, our work aims to bridge this critical gap. Specifically, our questions are:

**Can we efficiently extract MLP-related link prediction knowledge from GNNs? **

In this work, we focus on exploring, borrowing, and proposing cross-model (GNN to MLP) refinement techniques for link prediction settings. We first explore two KD methods that directly align students and teachers: (i) probabilistic prediction matching based on the logarithm of link presence ( Hinton et al., 2015 ), and (ii) representational matching based on generated latent node representations ( Gou et al., 2021 ). Empirically, however, we find that neither logarithm-based matching nor representation-based matching is sufficient to extract sufficient knowledge for student models to perform well on link prediction tasks. We hypothesize that the reason for the poor performance of these two KD methods is that link prediction, unlike node classification, relies heavily on graph topology information (Mart ́ınez et al., 2016; Zhang & Chen, 2018; Yun et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022b), which direct methods do not capture well.

To address this problem, we propose a relational KD framework, the LLP: Our main intuition is that we do not focus on the matching of individual node pairs or node representations, but rather on the matching of relationships between each (anchor) node and other (context) nodes in the graph. Given the anchor node-centered relation knowledge, i.e., the link existence probability between the anchor node and each context node predicted by the teacher model, LLP refines it into the student model through two matching methods: (i) rank-based matching and (ii) distribution-based matching. More specifically, rank-based matching provides the student model with rank losses of all contextual nodes relative to anchor nodes, preserving key rank information directly relevant to downstream link prediction use cases, such as user contextual friend recommendations (Sankar et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022) or item recommendations (Ying et al., 2018a; He et al., 2020). Distribution-based matching, on the other hand, provides the student model with a link probability distribution of context nodes conditioned on anchor nodes. Importantly, distribution-based matching is complementary to rank-based matching in that it provides auxiliary information about the relative values of probabilities and the magnitude of differences. To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed LLP, we conduct experiments on 8 public benchmarks. In addition to the standard transduction setting for the graph task, we also designed a more realistic setting that mimics real-world (online) use cases of link prediction, which we call the production setting. Across all datasets, LLP outperforms standalone MLP by an average of 18.18 points in the transduction setting and 12.01 points in the production setting; in the transduction setting, LLP outperforms teacher GNN on 7/8 datasets. Reassuringly, on cold-start nodes, LLP outperforms teacher GNN and independent MLP by an average of 25.29 and 9.42 Hits@20, respectively. Finally, LLP inference is significantly faster than GNNs, e.g. 70.68x faster on the large Collab dataset.

# Related work and background

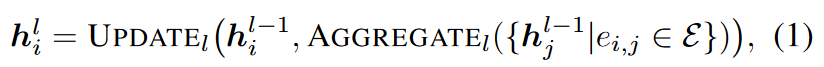

Link prediction using GNN. In this work, we apply the commonly used encoder-decoder framework for the link prediction task (Kipf & Welling, 2016b; Berg et al., 2017; Schlichtkrull et al., 2018; Ying et al., 2018a; Davidson et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2021; Yun et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2022b), which is based on GNN The encoder learns node representations and the decoder predicts link existence probabilities. Most GNNs operate under a message passing framework, where the model iteratively updates the representation hi of each node i by obtaining information about its neighbors. That is to say, the representation of nodes in layer l is through aggregation learning operations and update operations:

Among them, AGGREGATE combines or aggregates local neighbor features, and UPDATE is a learnable transformation $h_i^0=x_i$. The link prediction decoder uses the node representation of the previous layer, i.e., hi of i∈V, to predict the link probability between node pair i and j:

where σ represents the Sigmoid operation. In this work, following most of the state-of-the-art link prediction literature (Zhang et al., 2021a; Tsitsulin et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2022b; Wang et al., 2021), we adopt Hadamard product and MLP as the link prediction DECODER for all methods.

Knowledge distillation of GNN. Knowledge Distillation (KD) aims to transfer knowledge from a high-capacity and high-accuracy teacher model to a lightweight student model, often used in resource-constrained environments. KD methods have shown the potential to significantly reduce model complexity while sacrificing little to no task performance. Since GNNs are slow due to data dependence caused by neighbor aggregation, graph-based KD methods usually distill GNNs onto MLPs, which are widely used in large-scale industrial applications due to their significantly improved efficiency and scalability. For example, Zheng et al. proposed a KD-based framework to rediscover the missing graph structure information of MLPs, which improved the model’s generalization ability on the node classification task on cold-start nodes. Existing KD methods based on graph data mainly focus on node-level and graph-level tasks, while applying KD to link prediction has not yet been explored. Our work focuses on extracting link prediction relevant information from GNN teachers to MLP students and studies various KD strategies to align student and teacher predictions.

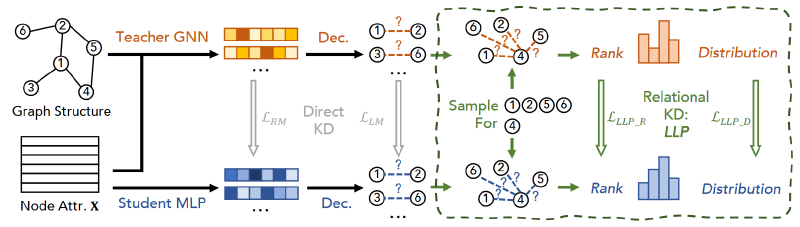

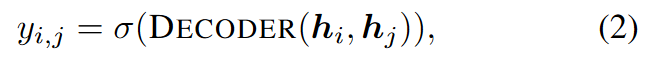

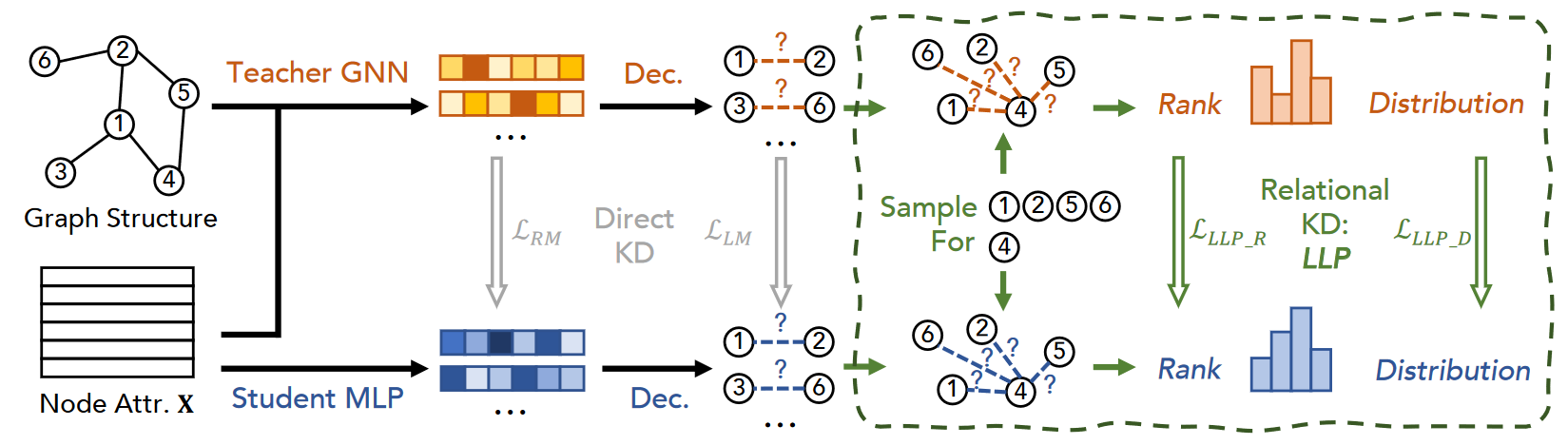

# Cross-model knowledge distillation for link prediction

In this section, we propose and discuss several knowledge distillation methods across models from teacher GNN to student MLP for the purpose of link prediction. In all cases, we aim to guide student MLPs using artifacts produced by the GNN teacher, in addition to any available training labels (ai,j with respect to link presence). We first adopt two direct knowledge distillation (KD) methods: logic-based matching and representation-based matching, and adapt them to the link prediction task; we call these methods direct because they involve directly matching sample predictions between teachers and students. Next, we propose and introduce our proposed relational KD framework, LLP (Linkless Link Prediction), and propose two matching strategies to distill additional topological structure information into the student model. We call these methods relational because they require relationships between teachers and students to be maintained across samples (Park et al., 2019). Figure 1 summarizes our proposal.

# Direct method

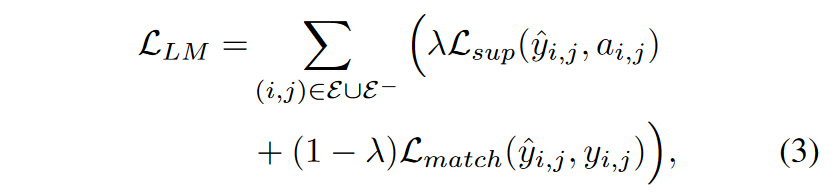

Logical matching is a straightforward strategy for knowledge distillation from teacher to student, where it directly aims to teach students to generalize as well as teachers on downstream tasks. It was proposed by Hinton et al. (2015) and remains one of the most widely used KD methods in various tasks. Phuong and Lampert (2019) and Ji and Zhu (2020) theoretically analyzed its effectiveness. Furthermore, it has also been shown to be effective in knowledge transfer on graph data. For example, Zhang et al. (2021b) used soft logic generated by teacher GNN to guide student MLP and achieved strong performance on node classification tasks. Similarly, we generate soft scores yi,j for candidate edges (i, j) and train the student to predict ˆyi,j matching this target:

Representation matching is another straightforward distillation method where we aim to align the student’s learned latent node embedding space with the teacher’s. Since this KD training signal only optimizes the encoder part of the student model, it must be used with Lsup so that the student decoder also receives gradients and is optimized:

# Link prediction for relation distillation

motivation. The direct methods described above require student models to directly match node-level or link-level artifacts. However, one might ask: is matching these sufficient for the link prediction task? This is particularly relevant in the context of considering that most link prediction applications involve tasks where ranking candidate targets of a source node or an anchor node is the task of interest, i.e. in a user-item graph the predictor must rank a set of candidate items from the user’s perspective. These contexts involve reasoning over multiple relationship- or link-level samples simultaneously, suggesting that matching across these relationships may be more suitable for target link prediction tasks than direct node-level or link-level approaches.

Furthermore, some works (Zhang & Chen, 2018; Yun et al., 2021) show that graph structure information is crucial for the link prediction task. For example, heuristic link prediction methods often show competitive performance compared to GNNs and have been the cornerstone of accurate link prediction before neural graph methods. Most heuristics measure the score of a target node pair based only on graph structure information (e.g., common neighbors and shortest paths). In addition, some recent works (Zhang & Chen, 2017, 2018; Li et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2022b) also show that including topological information, such as local subgraphs, distances from anchor nodes, or enhanced links, can significantly improve the performance of GNNs on link-level tasks. Observing that most successful link prediction methods involve using relation information rather than just two nodes, we also adopt this intuition in the context of distillation and propose our relation KD for link prediction.

# Connectionless link prediction

Based on our intuitive understanding of preserving relational knowledge, we propose a new relational distillation framework called Linkless Link Prediction, or LLP. Rather than focusing on matching individual node pair scores or node representations, LLP focuses on distilling knowledge of each node’s relationships with other nodes in the graph; we call the former anchor nodes and the latter context nodes. For each node in the graph, when it serves as an anchor node, our goal is to provide the student MLP model with knowledge of its relationships with a set of context nodes. Each node can serve as an anchor node or as a context node for other anchor nodes.

Let v represent the anchor node, and Cv represent the set of context nodes corresponding to v. We represent the probability between v predicted by the teacher model and each node in Cv as Yv = {yv,i | i ∈ Cv}. Likewise, we denote the student model’s predictions of these as Yv = {yv,i | i ∈ Cv}. To effectively distill relational knowledge from Yv to Yv, we propose two relational matching objectives to train LLP: ranking-based matching and distribution-based matching, which we will introduce below.

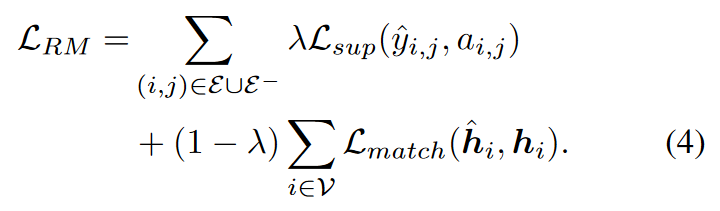

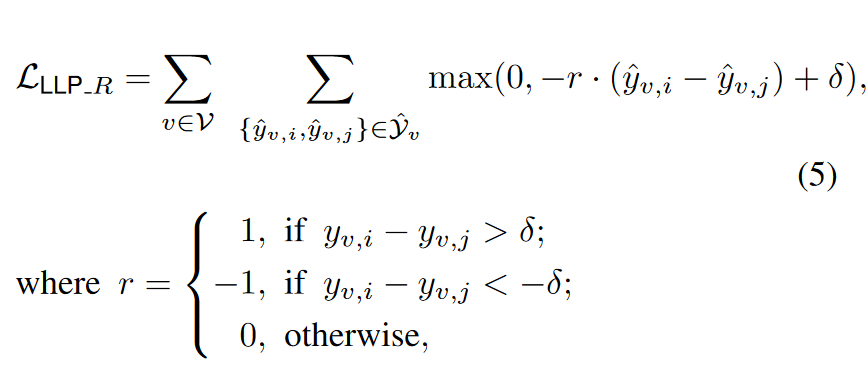

Rank-based Matching. As mentioned in Section 3.2, link prediction is usually viewed as a ranking task, requiring the model to rank relevant candidates based on a seed node, such as in the user-item graph setting, where the predictor must rank a set of candidate items from the user’s perspective. Therefore, we argue that, unlike matching independent logic, matching teacher-induced rankings can more directly teach students knowledge about the relationships of context nodes relative to anchor nodes. For example, for a specific user, item A should be ranked before item C, and item C should be ranked before item B. To incorporate this ranking-based intuition into the training objective, we employ a modified margin-based ranking loss to train the student with the ranking logarithm of the teacher GNN. Specifically, we enumerate all pairs of predicted probabilities in 𝑌^𝑣Y^v and supervise with the corresponding pairs in 𝑌𝑣Y**v. Right now:

δ is the marginal hyperparameter, usually a very small value (e.g. 0.05). Note that the above loss is different from the traditional margin-based ranking loss because it has a condition of 𝑟=0r=0 (resulting in a constant loss) on logarithmic pairs where the teacher GNN gives similar probabilities, i.e. ∣𝑦𝑣, −𝑦𝑣,𝑗∣<𝛿∣y**v,i−y**v,j∣<δ. This design effectively prevents the student model from trying to distinguish small probability differences that teachers may have due to noise; without this condition, the loss will convey binary information regardless of how small the difference is. We also demonstrate empirically the necessity of this design through Table D.16.

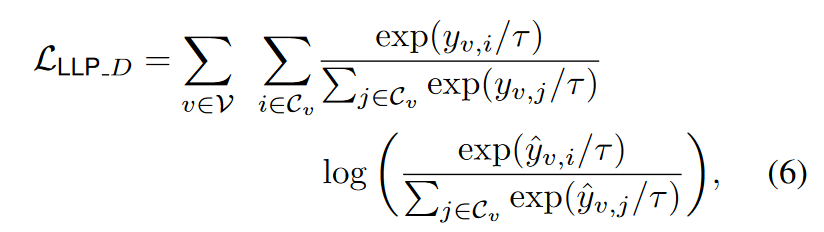

Distribution-based Matching. Although ranking-based matching can effectively teach student models relational ranking information, we observe that it does not fully utilize the value information in 𝑌𝑣Y**v. For example, for a particular user, item A should be ranked much higher than item C, which should be only slightly higher than item B. Although the logical matching introduced in Section 3.1 seems suitable here, we observe that its link-level matching strategy only facilitates matching information on scattered node pairs, rather than focusing on contextual relations on anchor nodes—empirically, we also find that its effect is limited. Therefore, in order to achieve relationship value matching centered on the anchor node, we further propose a distribution-based matching scheme, which utilizes the KL divergence between the teacher’s prediction 𝑌𝑣Y**v and the student’s prediction 𝑌^𝑣Y^v, centered on each anchor node 𝑣v. Specifically, we define it as:

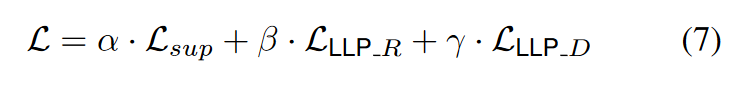

When training LLP, in addition to the ground truth label loss, we jointly optimize the ranking-based matching loss and the distribution-based matching loss. Therefore, the overall training loss adopted by LLP for students is

# Experimental evaluation

# Experimental settings

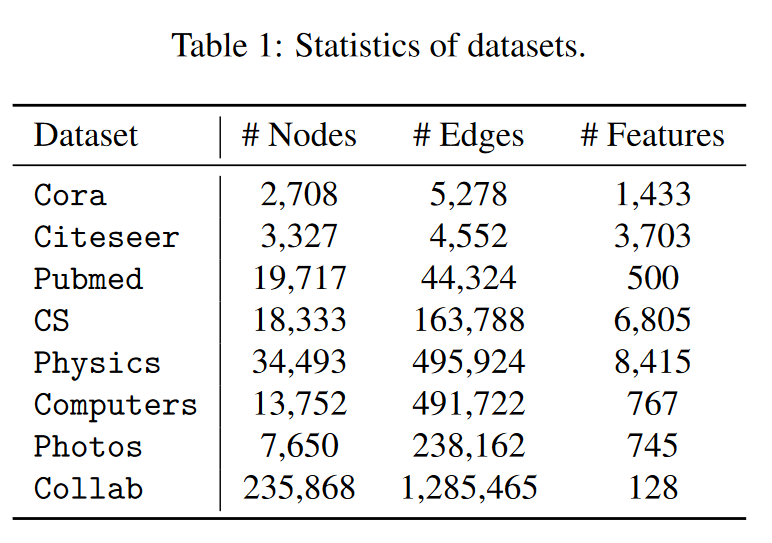

Assessment settings. To comprehensively evaluate our proposed LLP and baseline methods in the link prediction task, we conducted experiments in both transduction and production settings. For the transduction setting, all nodes in the graph are observable in the training/validation/test sets. Following previous studies (Zhang & Chen, 2018; Chami et al., 2019; Cai et al., 2021), we randomly sample 5%/15% of links from the graph with the same number of edgeless node pairs as the validation set/test set on the non-OGB dataset. Validation/testing links will be masked from the training graph. For the OGB dataset, we follow its official train/validation/test split method (Wang et al., 2020a). In addition to the transitional setup, we also designed a more realistic setup to simulate actual link prediction use cases, which we call the production setup. In a production environment, new nodes appear in the test set, while the training and validation sets only observe previously existing nodes. Therefore, in this case, three types of node pairs (edges or no edges) will appear in the test set: existing-existing, existing-new, new-new, where the first type is similar to the test edges in the transductive setting, and the last two types are similar to the inductive setting used in some recent studies (Bojchevski & G ̈ unnemann, 2017; Hao et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021b). However, in real application cases, such as the growth of social networks or online platforms, these three types of edges will appear in different proportions, so we evaluated all three types of edges. Note that we only conduct production experiments on non-OGB datasets because the OGB dataset is already time-split in its publicly released version. We elaborate further on the details of the production environment in Appendix C.

# Link prediction results

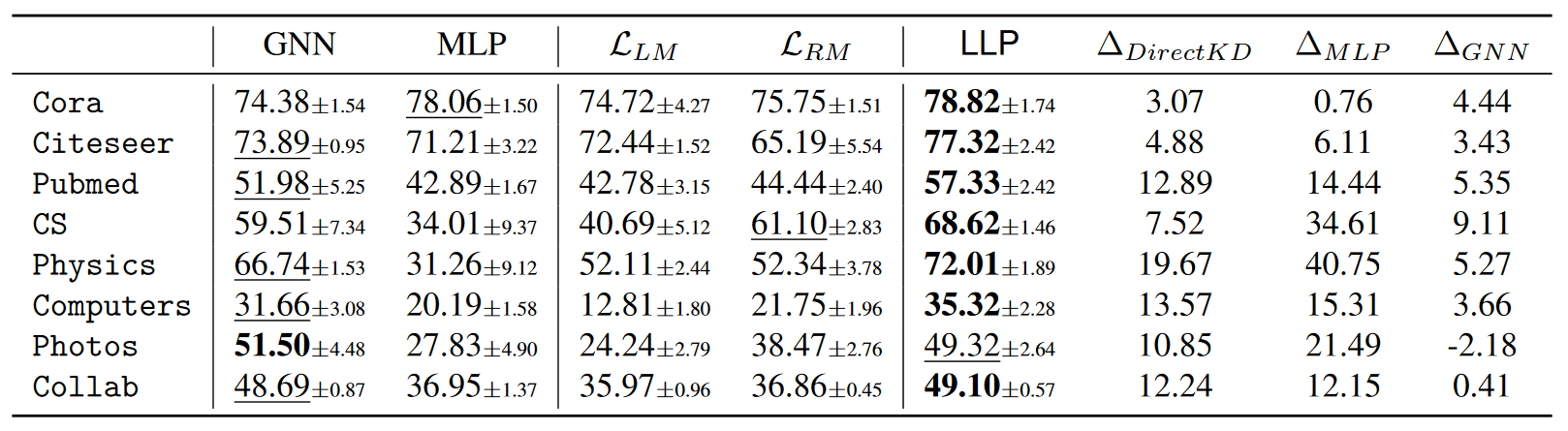

Transductive Setting

- This is a standard setting in link prediction, where all nodes in the training, validation and test sets are visible on the training graph, but a portion of the positive links are masked for the validation and test sets.

- In this setting, the model can see the entire graph structure during training, including all nodes and edges, except those links that are explicitly masked for evaluation.

From Table 2, we also find that the performance of LLP is significantly improved over teacher GNN on some datasets. We hypothesize that there are two reasons for this improvement. First, when node features are sufficiently informative for link prediction, the student MLP model already has significant learning capabilities. For example, on the Cora dataset, MLP can already produce better prediction performance than GNN. Another reason is that relational KD provides relational structure knowledge from GNN to MLP, which provides additional valuable knowledge to MLP. Recent research on knowledge extraction (Allen-Zhu & Li, 2020; Guo et al., 2022) has similar findings, that is, combining different perspectives from different models helps improve the performance of the model.

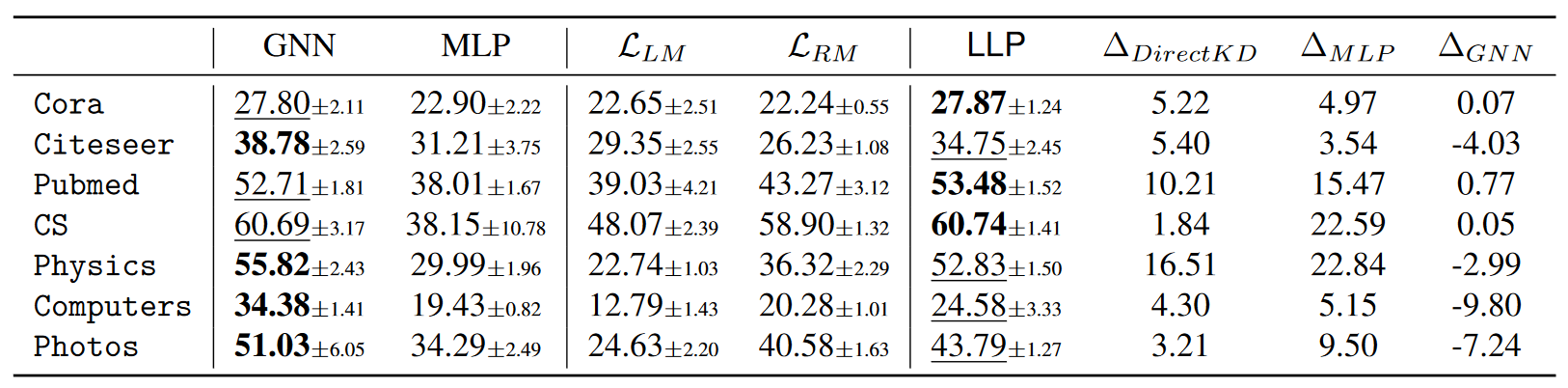

Production Setting

- This is a setting that is closer to actual application scenarios and simulates actual link prediction use cases, such as user friend recommendations on social network platforms, where new users and friend relationships appear frequently.

- In production settings, new nodes and edges may appear in the test set that were not visible during the training phase. This setting considers three categories of node pairs: existing-existing, existing-new, and new-new, corresponding respectively to node pairs that already exist in the training set, node pairs with at least one new node, and node pairs consisting entirely of new nodes.

# Inference speed

We evaluate LLP compared with other common GNN inference acceleration methods, which mainly focus on hardware and algorithms to reduce computational consumption, such as pruning (Zhou et al., 2021) and quantization (Zhao et al., 2020; Tailor et al., 2020). Following the experimental setup of Zhang et al. (2021b), we measured the inductive reasoning time in the graph. We evaluated 4 common GNN inference acceleration methods: (i) SAGE (Hamilton et al., 2017), (ii) quantized SAGE from float32 to int8 (QSAGE) (Zhao et al., 2020; Tailor et al., 2020), (iii) SAGE with 50% weight removed (PSAGE) (Zhou et al., 2021; Chen) et al., 2021c), and (iv) neighbor sampling SAGE with 15 fan-outs removed. Figure 2 shows the results of Collab on the large-scale OGB dataset. We can see that LLP is 70.68x faster on Collab compared to SAGE. LLP still achieves a 15.05x speedup compared to the best speedup method “Neighbor Sampling” (which reduces graph dependence but cannot eliminate it like LLP). This is because all these inference acceleration methods still rely on graph structures. From the lower graph of Figure 2, we can further observe that LLP outperforms GNN and other inference acceleration methods.

# Link prediction results of cold start nodes

Handling cold-start nodes (emerging edgeless nodes) is a common challenge in recommendation and information retrieval applications (Li et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2021). Without these edges, GNNs do not work well because they rely heavily on neighbor information. On the other hand, MLP which does not use any graph topology information is arguably more suitable. Here, we simulate a cold-start setup, i.e., all new edges are removed during the testing phase of a production setup, i.e., all emerging nodes are isolated (see Appendix C for more details). Table 4 shows the performance of LLP, independent MLP and teacher GNN on cold start nodes. We observe that on Hits@20, LLP consistently outperforms GNN and MLP on average by 25.29 and 9.42, respectively. We also further present another related study comparing LLP with cold start nodes in Appendix D.8.

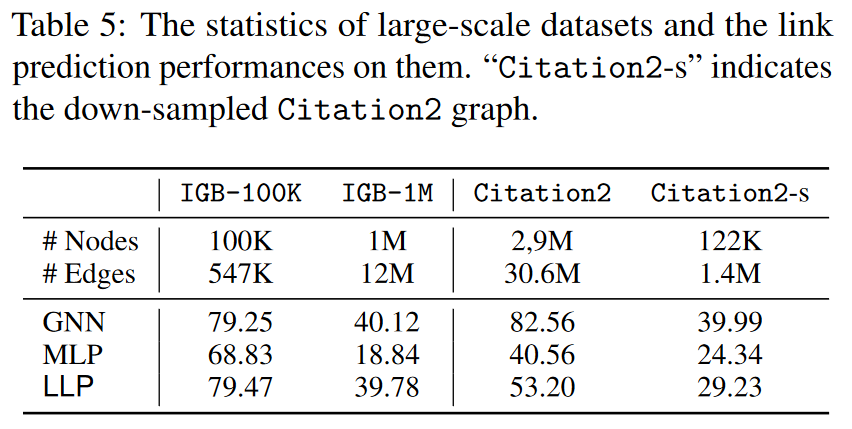

# Link prediction results on large-scale data sets

In addition to Collab, we also conduct experiments on three recently proposed large-scale graph benchmarks: IGB-100K, IGB-1M (Khatua et al., 2023), and Citation2 (Wang et al., 2020a; Mikolov et al., 2013). Data set statistics and link prediction results (Hits@200) are shown in Table 5. On the IGB dataset, we observe that LLP can produce competitive results on both datasets, which further demonstrates the ability of LLP to obtain complex link prediction-related knowledge from large-scale graphs. On the other hand, the results for Citation2 show a different pattern. Although LLP performs significantly better than MLP, its performance is still far behind GNN.

We hypothesize that the different performance patterns on Citation2 are due to the unique distribution of the dataset. To verify our hypothesis, we further conducted experiments on a sampled version of Citation2 (column “Citation2-s” in Table 5). Specifically, we downsampled Citation2 to produce a smaller version (similar in size to Collab). We used a random walk-based sampling method, which has been shown to preserve the properties of the original graph (Leskovec & Faloutsos, 2006). From Table 5, we observe that the performance patterns of Citation2 and Citation2-s are very similar, which verifies our hypothesis that the performance gap between LLP and GNN is caused by the distribution of the dataset itself rather than by other factors such as the size of the graph. When comparing the results for Photos and Collab in Table 2, we also find a similar situation, but the opposite is true: on the larger dataset (Collab), LLP performs better than GNN, but on the smaller dataset (Photos), LLP performs slightly worse than GNN. In summary, the effectiveness of LLP may vary on different datasets but is not sensitive to the size of the graph.

# Ablation experiment

Validity of LLLP R and LLLP D. Since our proposed LLP contains two matching strategies, namely rank-based matching and distribution-based matching, we evaluate their effectiveness by removing them from the LLP. Additionally, we conducted further evaluation by removing Lsup, i.e. using only one of the matching losses as the overall loss for LLP. Table 6 shows the performance comparison results of these settings with full LLP, independent MLP, and teacher GNN on Pubmed and CS datasets. We note that both rank-based matching and distribution-based matching contribute significantly to the overall performance. In the transductive setting, the two loss terms themselves (bottom two rows) already outperform the teacher GNN.

In a production environment, matching loss alone outperforms MLP, and when adding Lsup can achieve comparable performance to GNN. In summary, both rank-based matching and distribution-based matching can effectively refine relational knowledge and achieve optimal performance through complementation.

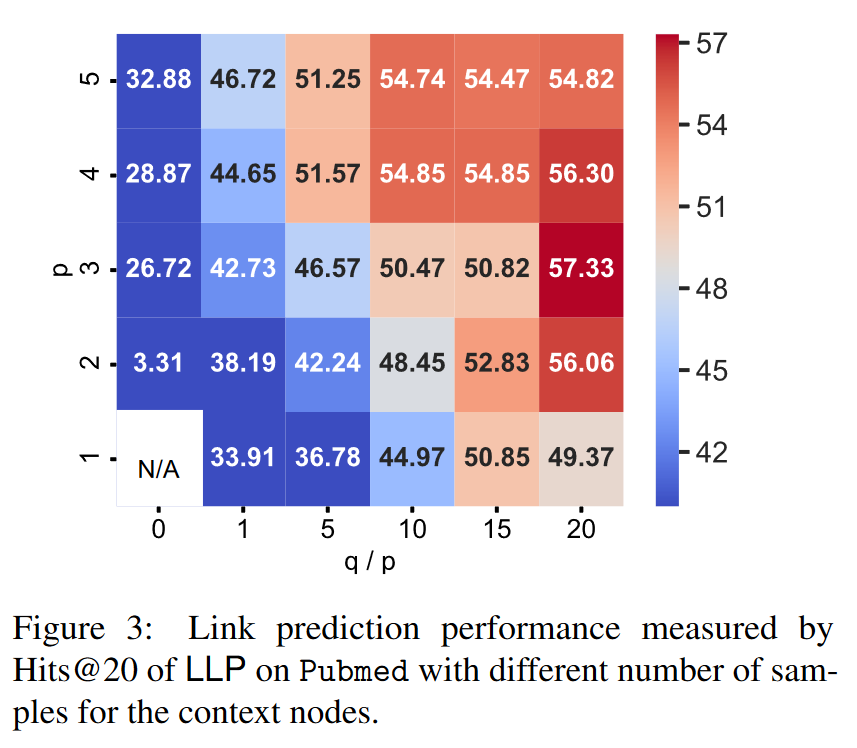

Figure 3 shows the link prediction performance of LLP on Pubmed under different numbers of context node samples (p local samples and q random samples). To facilitate tuning of hyperparameters, we set q to be a multiple of p, as shown on the x-axis of Figure 3. We observe that LLPs with a smaller number of random samples have poorer link prediction performance, indicating that preserving global relationships is necessary for the proposed relationship KD. In general, heat maps show a clear trend, making the optimal values easy to locate.

# Summarize

Our work addresses problems related to the large-scale application of GNNs for link prediction. We note that these models have higher latency at inference time due to non-3D data dependencies. To this end, we explore a cross-model refinement approach from teacher GNN to student MLP models, which has advantages in inference time. We first apply two direct log-matching and representation-matching KD methods to link prediction and observe their inapplicability. In response, we introduce the relational KD framework LLP, which proposes rank-based matching and distribution-based matching goals that complement each other and force students to retain key information of contextual relationships between anchor nodes. Our experiments show that LLP achieves MLP-level speedups (70.68x higher than GNN) while improving link prediction performance by 18.18 and 12.01 percentage points over MLP in the transduction and production settings respectively, performing as well as or better than the teacher GNN on 7/8 datasets in the transduction setting and 3/6 datasets in the production setting, and on cold-start nodes. The Hits@20 improvement is a significant 25.29 percentage points.